The 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games were a seminal moment for modern Japan. This was the first prestigious sporting event to be held in Asia. And since it was televised to the world, the occasion offered Japan a chance to present itself as a modern and advanced nation. “The opportunity to host the Games allowed the country’s innovative architects, designers and engineers to blossom on the international stage,” explains Simon Wright, director of programming at Japan House London, as he presents Tokyo 1964: Designing Tomorrow. “The Games provided a focal point for the whole nation to look towards regeneration and creating a new international face.”

Tokyo 1964 is the latest exhibition to be staged at the London gallery and cultural centre. The show has been created in collaboration with architecture writers and curators Yamashita Megumi and David Philips and produced with the support of the Japan Sport Council. Staged in the lower gallery, Tokyo 1964 explores the cultural legacy behind the Games through original objects, artwork and posters, architectural models, photography and film to great effect.

Read more: Online Japanese art exhibitions that are (almost) as good as the real thing

Strong branding and a clear design vision were pivotal to the Olympics so much so that a design committee was swiftly set-up when Tokyo won the completion to stage the event in 1959. The logotype, typography and pictograms all followed a unified style. Even the uniforms for the Games, including a furisode kimono worn by the medal presenters, were suitably branded.

Preparation for the Games crucially considered imagining a new urban landscape for Tokyo with elevated super-highways to embrace the motor car as a symbol of progress. Even the cutting-edge stadium complex was made to be car friendly. Meanwhile, the high-speed Tōkaidō Shinkansen bullet train was launched to connect distant regions to the capital.

Precision timepiece maker Seiko became the official timer of the Games, a position previously reserved for established Swiss watchmakers. The 1964 Olympics were also the first to be televised worldwide live via Syncon 3, the world’s first geostationary satellite. These feats helped secure the international reputation of Japanese manufacturing for the future.

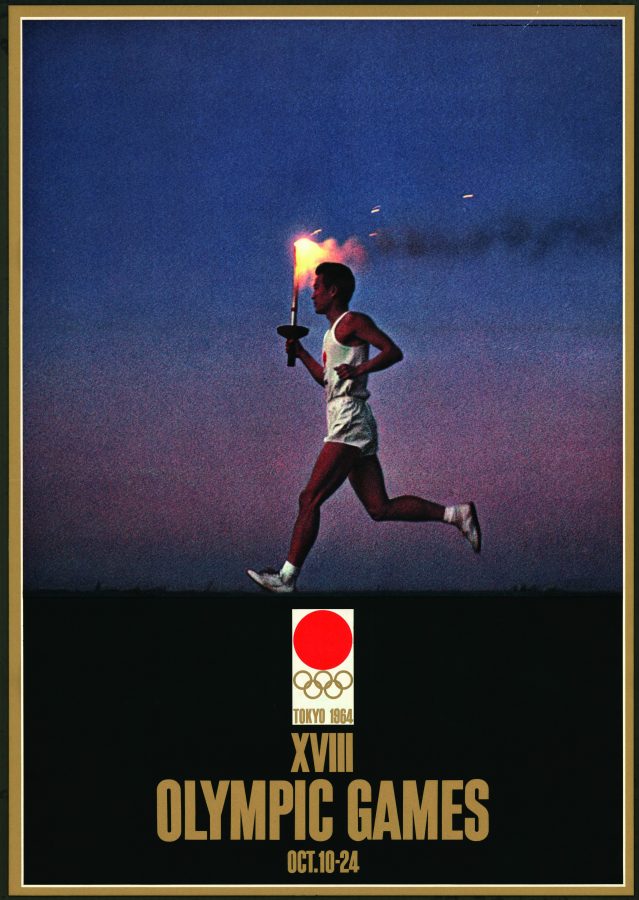

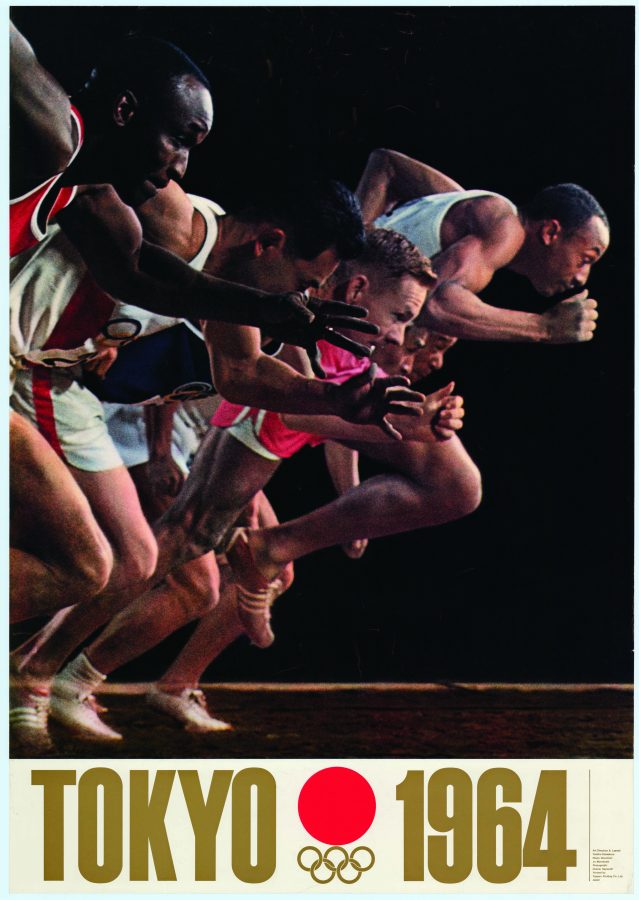

The upbeat and optimistic mood leading up to the Games encouraged the designers and architects involved to be as inventive and radical as possible. Promotional posters by the renowned graphic designer Kamekura Yūsaku, for instance, worked with photographic images for the first time at an Olympic event. What’s more, since few attending the Games would have ever been to Japan, to combat the language barrier, the graphics team created simple silhouette style pictograms for the various sports and facilities. They even published English language city guides and tourist maps.

One of the most exciting legacies of the Tokyo Games, though, is the stadia architecture. The Olympic Memorial Tower and Yoyogi National Stadium by illustrious local architects Ashihara Nobuyoshi and Tange Kenzō respectively are particularly brave and bold with exhibits of drawings, photographs and architectural models depicting the complexity of the construction. The stacked brutalist silhouette of the Tower and dramatic suspended roof of Yoyogi placed Japan at the forefront of debate surrounding modernism for decades to come.

The conceptual roots of these designs can be traced to 1960, when the Japanese government funded the World Design Conference. They invited leading global figures in architecture and design – the likes of Louis Kahn, Jean Prouvé, Paul Rand, Saul Bass – to come to Tokyo and discuss and debate how corporate identity and visual language might be utilised in large organisations and events.

It was at this historical conference where the Metabolism manifesto was conceived. This avant-garde Japanese architectural movement promoted the idea of flexible cities as a reflection of progress. Metabolism argued for cities and buildings to be dynamic growing entities, and that this fluidity needs to be built into the urban structure – a concept that happens to be at the forefront of debate today as we emerge from the current pandemic. The architecture of the 1964 Games was one of the first manifestations of this type of construction.

The Tokyo Games helped create a unified language by which to communicate the Olympics. “It became the blueprint for subsequent major international sporting events,” says Wright. And it succeeded in signifying a new dawn for Japan. A generation who had been influenced by American and European modernism had now found a distinct Japanese creative expression. The inventive collage technique employed in Ichikawa Kon’s documentary film of the Games, screened at Japan House London, perfectly captures the spirit of 1964.

“Tokyo 1964: Designing Tomorrow” will be at Japan House London from 5 August to 7 November 2021.