How to reinvent an icon? As an emblem of Japan’s national and cultural identity, the kimono might seem untouchable: a garment so rich in symbolism and history that any modification would surely be sacrilege. But for contemporary Japanese fashion and textile designers – who wore them while growing up, swathed in elaborate waist sashes (obi) and heavy folded fabrics – the kimono represents an irresistible challenge: how can this ceremonial dress be freed from convention, while keeping its identity intact?

Jōtarō Saitō. Takahashi Hiroko. Yoshikimono. These are just some of the new names to watch: the designers for whom kimono is a concept to be subverted, to be picked apart and reimagined as a playful, flexible garment. Yoshikimono is led by Yoshiki Hayashi, who comes from a family of traditional kimono merchants – yet he brings a punk sensibility with risqué hemlines and manga-print fabrics. Takahashi Hiroko specialises in yukata (an informal cotton style of kimono) but with edgy geometric and monochrome designs. And Jōtarō Saitō, whose colourful couture creations regularly adorn the catwalks of Tokyo Fashion Week, made headlines when he recently designed a kimono for Lady Gaga: a bubblegum-pink robe, tied with a sequined obi.

“Japan is currently witnessing a resurgence of interest in the kimono,” explains Anna Jackson, fashion historian and keeper of the Asian Department at London’s V&A museum. “Today’s wearers appreciate kimono not as a form of tradition, but as a dynamic item of fashion.”

The V&A’s ‘Kimono: Kyoto to Catwalk’, an exhibition curated by Jackson, delves into the design – and redesign – of the garment, through pieces that span from the 1600s to the present day. Alongside priceless silk designs with delicate embroidery and ornate calligraphy – beloved in 17th-century Kyoto – the gallery reveals the artistry of contemporary incarnations.

One such kimono is Matsubara Yoshichi’s ‘Flight’ (1990), a midnight-blue robe which is seemingly studded with pinpricks of light. To create the effect, Yoshichi reinvented the traditional katazome technique which uses rice paste as a dye barrier. In the 1600s, katazome was used to draw sharp outlines of cherry blossom and soaring cranes – classic symbols of renewal and longevity – but Yoshichi dots and smudges it to create blurry, bright ‘holes’ in the rich navy colour.

One such kimono is Matsubara Yoshichi’s ‘Flight’ (1990), a midnight-blue robe which is seemingly studded with pinpricks of light. To create the effect, Yoshichi reinvented the traditional katazome technique which uses rice paste as a dye barrier. In the 1600s, katazome was used to draw sharp outlines of cherry blossom and soaring cranes – classic symbols of renewal and longevity – but Yoshichi dots and smudges it to create blurry, bright ‘holes’ in the rich navy colour.

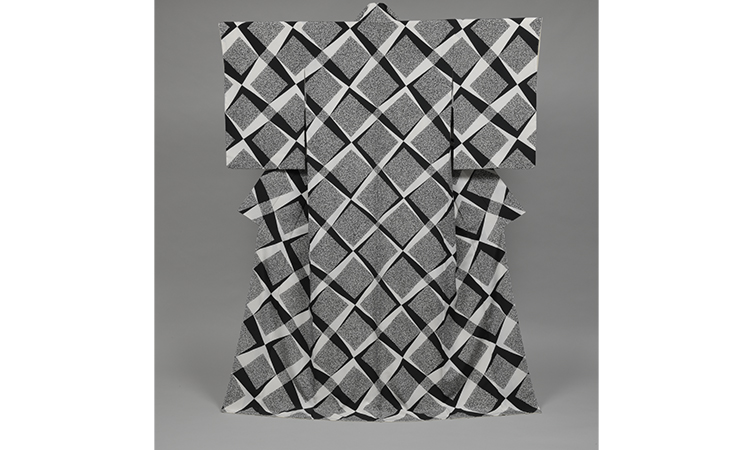

Moriguchi Kunihiko, too, has developed his own dye-resist technique. For his striking black-and-white ‘Beyond’ design (2005), the former graphic designer sprinkled the silk with dry rice particles – creating a dappled effect that’s almost hypnotic up-close.

For many couturiers, now is the time to cast silk aside – in favour of lighter materials for a more flexible, unisex style. Yamaguchi Genbei, for example, favours hemp (taima-fu) – a sustainable, eco-friendly fibre. His Summer Kimono (2019) was created as part of the Majotae Project, which explores how hemp could be the future of Japanese clothing manufacture: it’s low carbon, commercially-viable, and perfectly suited to grow in the country’s climate.

Stylist Akira Times, meanwhile, reveals the sheer joy of a ‘mix-and-match’ approach to dressing: by combining modern robes with vintage obi, and classic silks with pop-art motifs. His ‘Kimono Times’ ensemble (2017) blurs the boundaries between old and new, east and west – yet it is still proudly, unmistakably, a kimono.

“One of the pleasures of curating the exhibition has been getting to know these modern kimono makers,” says Jackson. “This generation has reclaimed it as an item of fashionable dress – valued as a unique garment within an increasingly globalised world.”

‘Kimono: Kyoto to Catwalk’ is now on at The V&A (South Kensington, London) – until 21 June 2020. From £16; vam.ac.uk

Style of the centuries: the evolution of the kimono

794 – The first incarnation emerged during the Heian period (794-1185), with an apron-style garment known as a mo.

1600s – By 1603, the start of the Edo period, kimono robes were worn by everybody in Japan – regardless of sex or social status. Kyoto was the centre of textile production and design.

1700s – New fashions emerged, led by Kyoto’s actors and courtesans – the celebrities of the time. Gradually, sleeves lengthened and waist sashes (obi) widened, forming the style that is most recognisable today.

1800s – When the Edo period ended in 1868, Japan embraced international trade. This sparked a new global craze for kimonos, stretching as far as New York and New Zealand.

1900s – After the Second World War, Japan looked to its past for stability. The wearing of kimonos declined, and it was used only as ceremonial costume.

2000s – Recently the kimono has witnessed a fashion revival – with contemporary designs, new production techniques, and a bold presence on the catwalk.

Read more: How to have a weekend of Japanese Culture in London.