The roiling, raging sea of Hokusai’s Great Wave seems to leap off the page with its ferocious energy. The inky black water, the bone-white breakers, the churning torrents caught in the act of destruction. The scene is so full of life, of motion: you can almost feel the spray on your face. It’s a surprise, then, to learn that it was captured not with a free-flowing brush – but with a blade and a printer’s block.

Two centuries ago, Japan embraced woodblock printing as a cheap way to duplicate fashion designs and celebrity portraits. But as carvers’ skills grew, it transformed into an artform all of its own – known as ukiyo-e, or ‘pictures of the floating world’. Landscapes, folk tales and beautiful women were favoured subjects; Hokusai’s Great Wave, produced in the 1830s, became one of the most famous examples – alongside works by Hiroshige, Kunisada and Kiyochika (to delve deeper, see this excellent primer).

The printing method was complex, but allowed for easy reproduction – indeed, it’s thought that 8,000 copies were made of Great Wave. First, the artist would draw their design on thin washi paper, which was then fixed face-down on cherry wood. Next, the cutter carved through the paper into the wood, destroying the drawing in the process – and from this ‘key-block’ more stamps would be made, a new one for every colour needed.

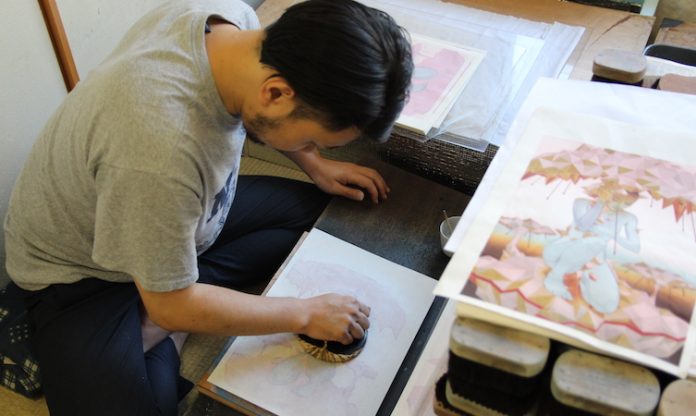

To make the outline of the image, the original carving was brushed with black ink, and the paper pressed onto it with a baren – a wide disc made from bamboo. Then, the coloured inks were applied using their unique blocks, until the piece was completely ‘filled in’. In this way, even the most intricate designs took mere moments to be duplicated.

Over the years, as mass-printing technology developed and Japanese artists discovered new disciplines, ukiyo-e fell out of favour. Some of the aesthetic qualities remained popular – such as colour-blocking (seen in 1920s Japanese Modernism) and strong outlines (a hallmark of manga) – but the printing process itself was consigned to the history books.

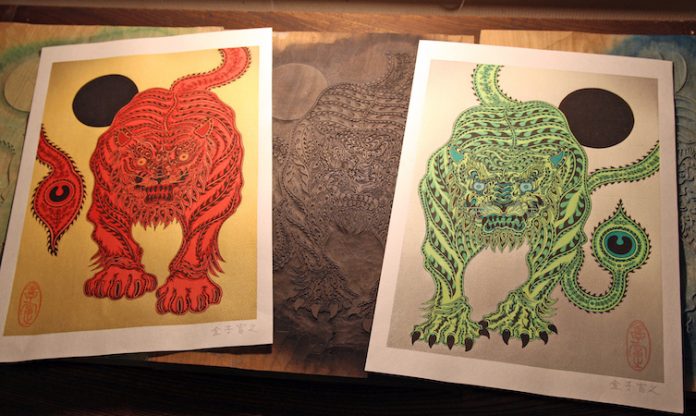

Until now. The Adachi Institute of Contemporary Ukiyo-e, in Tokyo, is buzzing with new ideas, new designs, and new artists exploring this ancient technique. Pairing modern designers with expert cutters, it nurtures fresh talent – such as Tomiyuki Kaneko, whose Red Tiger/Blue Tiger portrays a snarling mythical beast, produced entirely by hand. “When I first saw the woodcut print I felt there was a certain maturity to it,” says Saitama-born Kaneko, who usually paints or sketches his work. “I believe [it] comes from the aura and atmosphere carried on by the long history of woodcut prints.”

To scroll through the Adachi Institute’s archives is to see centuries-old methods brought bang up-to-date: in James Jean’s Parasola and The Editor, for example, ukiyo-e’s dreamy themes and female forms are combined with modern geometric shapes. Other creators are experimenting, too: when designing Lexus’s magnificent tattooed car, artist Claudia de Sabe revealed how the artform inspired its bold lines and rich golden hues.

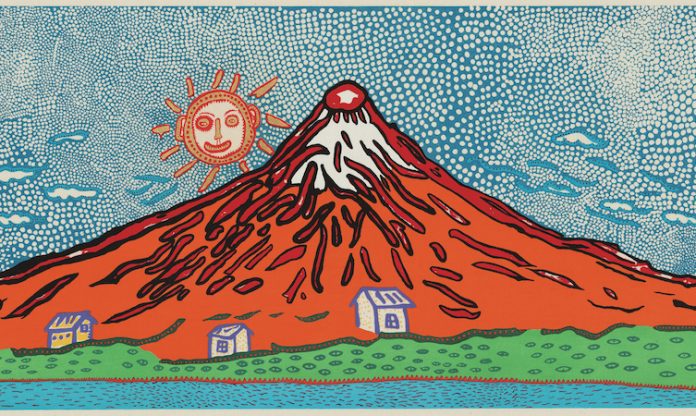

Even Matsumoto-born sculptor Yayoi Kusama – whose work has graced everywhere from London’s Tate Modern to The Met in New York – has tried ukiyo-e. The result of her first foray, Mt Fuji in Seven Colours, is a vibrant homage to Japan’s sacred mountain, strewn with her famous polka dot pattern.

Other artisans are turning to new materials: not only for baren discs (these days, aluminium or plastic are favoured, with ball bearings to keep the pressure smooth) but for the printing blocks themselves. Laser-cut wood is the preferred medium for illustrator Shinji Tsuchimochi, whose great-grandfather was a ukiyo-e artisan. For him, and many other modern makers, laser technology achieves a level of accuracy that no hand-carved designs ever could – but do the pieces still have the same soul? Judge his Rain Ginza for yourself.

At Takezasado, a woodcutting studio in Kyoto, modern-day prints are no longer limited to paper: they’re replicated on tableware, bags, book covers and wrapping paper. For some, such merchandise might commodify the artform, make it feel less authentic – but ukiyo-e has always been about mass-production, hasn’t it? Those 18th-century prints, the ones we pore over in museums and art galleries, were the kitsch of their day after all.

Whatever your view, whatever your taste, one thing is for certain: ukiyo-e is alive once again.