“I don’t look at design magazines much,” said Philippe Malouin, who recently joined the Lexus Design Award as a mentor for 2020.

With his striking beard and rugby player’s physique, Philippe is far from what you might call a stereotypical designer: he doesn’t wear black roll necks, he doesn’t sketch on demand and he isn’t pretentious in the slightest (but he does still use a Mac). His energy and passion for design, and the next generation of young designers, is infectious. “All those traditional ideas of what we think makes a good designer – good at sketching or great at using the computer – are changing. There are a million ways to make a good designer,” he says.

So, if he doesn’t read design magazines, what does he use to get those creative juices flowing? “Just photos. I spend days looking at photos, of anything and everything. We print thousands of them.” Indeed, his office-cum-workshop in Hackney, London, home to his eponymous design studio, has a wall lined with images. “It’s about understanding why. After comparing thousands of objects, you begin to develop your own good taste, and you can begin to understand why something is good and why something is bad. That curiosity and ability to educate yourself is certainly a quality I would be looking for in a Lexus Design Award entrant.”

Any aspiring designer should be excited at the prospect of having Philippe Malouin as a mentor. His experimental, hand-crafted approach has led to several design pieces that are genuinely unique. For example, he created a set of dinner plates and bowls with a grainy texture by building his own analogue 3D printer and pouring sugar into it. The resultant piles of sugar created the mould for the tableware.

Traditional design techniques, such as sketching and computer-aided design (CAD), still play their part in Philippe’s works, but making something by hand is important in kick-starting that creative process. “To get the initial spark, it’s interesting to do something by hand’, Philippe explains. “All you need to have are parameters: what material am I working in? What action should I take? If you have these two different parameters and perform experiments, you will make a very small discovery which leads you into the traditional design process. A lot of the time we don’t know where things are going.”

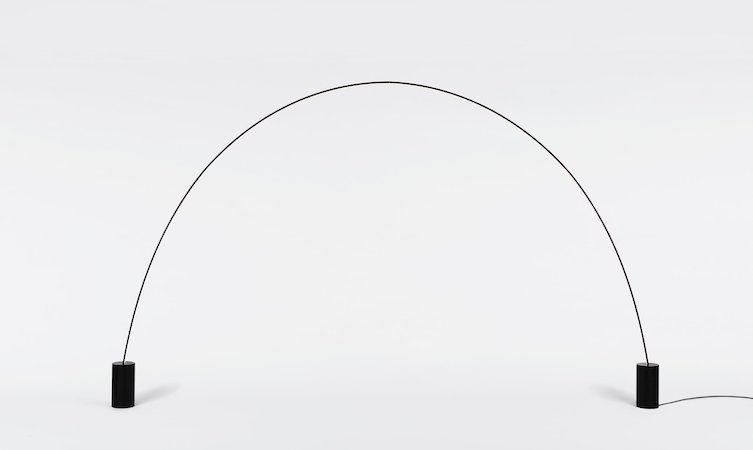

One of the best examples of this technique is Pole, which was made for American high-end lighting retailer Roll & Hill. Fashioned from aluminium and modular in its design, Pole is a flexible, configurable light that can be used to illuminate a huge variety of spaces: along walls, ceilings, floors. It is now in production and currently sold by Roll & Hill.

“[In a previous project we were asked] to do a design experiment in New York City where they basically gave us a credit card and a studio, and we bought all the materials we could within a kilometre radius. It was an experiment in design, not necessarily making something specific. At the end of it, we had some tent rods, LED tapes and bricks left. Not really thinking about it, I tied the LED tape on the tent rods, stretched it together and then placed it between the two bricks that were there… and that became this perfect piece of industrial design. I would never have come up with that had it not been through trial and error. It’s the only way to design something new, in my opinion.”

Hailing from a small town in Canada, and with little exposure the outside world, it wasn’t until Philippe took a four-year break from school and headed-off on an expedition of discovery around Europe that he became interested in design. On his travels, he met a huge variety of people with lots of different professions, but it was a chance meeting with an industrial designer got him interested.

Immersion in European life also helped to focus his career direction: “People live differently and consume differently in Europe than in America or Canada. In North America things are consumed more quickly, whereas in Europe a lot of people consume to make the right choice, and find something that truly represents who they are. I especially loved the furniture too. That’s why I wanted to become an industrial designer because I was interested in the different way in which objects are valued in Europe.”

This concept of value, and the permanence of an object, is also something which is inherent in Philippe’s design ethos. He works with the best quality materials possible to make something that will stand the test of time.

On his return to Canada, he undertook a foundation course at college that encouraged him to focus on industrial design. He studied that very subject at the University of Montreal, receiving a grant from the government to be schooled at the École Nationale Supérieure de Création Industrielle in Paris before earning honours at Design Academy Eindhoven.

It was at Eindhoven, and later as a practice mentor at the Royal College of Art, that Malouin developed a deep appreciation for nurturing the next crop of design talent: “I was lucky because all my teachers and mentors [at Eindhoven] were established designers that were very well known. I had different frames of view and different opportunities with all these designers I was working with.”

“Lexus having a design competition that allows international students to come together is also important. Collaboration is crucial, and I think a diverse, multi-cultural collaboration is the key. For example, [I think] someone from India teaming up with a kid from Cincinnati will probably create something together that will be more beneficial for a better tomorrow.”